Bela Lugosi

Bela Lugosi | |

|---|---|

Lugosi c. 1912 | |

| Born | Béla Ferenc Dezső Blaskó October 20, 1882 |

| Died | August 16, 1956 (aged 73) Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

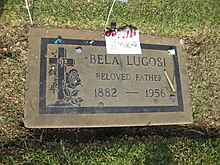

| Resting place | Holy Cross Cemetery |

| Other names | Arisztid Olt |

| Occupation | Actor |

| Years active | 1902–1956 |

| Spouses |

|

| Children | Bela George Lugosi |

| Website | belalugosi |

| Signature | |

| |

Béla Ferenc Dezső Blaskó (Hungarian: [ˈbeːlɒ ˈfɛrɛnt͡s ˈdɛʒøː ˈblɒʃkoː]; October 20, 1882 – August 16, 1956), known professionally as Bela Lugosi (/ləˈɡoʊsi/ lə-GOH-see; Hungarian: [ˈluɡoʃi]), was a Hungarian–American actor. He was best remembered for portraying Count Dracula in the horror film classic Dracula (1931), Ygor in Son of Frankenstein (1939) and his roles in many other horror films from 1931 through 1956.[1]

Lugosi began acting on the Hungarian stage in 1902. After playing in 172 productions in his native Hungary, Lugosi moved on to appear in Hungarian silent films in 1917. He had to suddenly emigrate to Germany after the failed Hungarian Communist Revolution of 1919 because of his former socialist activities (organizing a stage actors' union), leaving his first wife in the process. He acted in several films in Weimar Germany, before arriving in New Orleans as a seaman on a merchant ship, then making his way north to New York City and Ellis Island.

In 1927, he starred as Count Dracula in a Broadway adaptation of Bram Stoker's novel, moving with the play to the West Coast in 1928 and settling down in Hollywood.[2] He later starred in the 1931 film version of Dracula directed by Tod Browning and produced by Universal Pictures. Through the 1930s, he occupied an important niche in horror films, but his notoriety as Dracula and thick Hungarian accent greatly limited the roles offered to him, and he unsuccessfully tried for years to avoid typecasting.

He co-starred in a number of films with Boris Karloff, who was able to demand top billing. To his frustration, Lugosi, a charter member of the American Screen Actors Guild, was increasingly restricted to mad scientist roles because of his inability to speak English more clearly. He was kept employed by the studios principally so that they could put his name on the posters. Among his teamings with Karloff, he performed major roles only in The Black Cat (1934), The Raven (1935), and Son of Frankenstein (1939); even in The Raven, Karloff received top billing despite Lugosi performing the lead role.

By this time, Lugosi had been receiving regular medication for sciatic neuritis, and he became addicted to doctor-prescribed morphine and methadone. This drug dependence (and his gradually worsening alcoholism) was becoming apparent to producers, and after 1948's Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein, the offers dwindled to parts in low-budget films; some of these were directed by Ed Wood, including a brief appearance in Wood's Plan 9 from Outer Space (released posthumously in 1957).[3]

Lugosi married five times and had one son, Bela G. Lugosi (with his fourth wife, Lillian).[3]

Early life

[edit]

Lugosi, the youngest of four children,[4] was born Béla Ferenc Dezső Blaskó in 1882 in Lugos, Kingdom of Hungary (now Lugoj, Romania) to Hungarian father István Blaskó, a baker who later became a banker,[5] and Serbian-born mother Paula de Vojnich.[6] He was raised in a Catholic family.[7]

At the age of 12, Lugosi dropped out of school and left home to work at a succession of manual labor jobs.[4] His father died during his absence. He began his stage acting career in 1902.[8] His earliest known performances are from provincial theatres in the 1903–04 season, playing small roles in several plays and operettas.[8] He took the last name "Lugosi" in 1903 to honor his birthplace,[4][9] and went on to perform in Shakespearean plays. After moving to Budapest in 1911, he played dozens of roles with the National Theatre of Hungary between 1913 and 1919. Although Lugosi would later claim that he "became the leading actor of Hungary's Royal National Theatre", many of his roles there were small or supporting parts, which led him to enter the Hungarian film industry.[10]

During World War I, he served as an infantry officer in the Austro-Hungarian Army Imperial and Royal 43rd Infantry Regiment[11] from 1914 to 1916, with the rank of lieutenant. He was awarded the Wound Medal for wounds he sustained while serving on the Russian front.[4] Returning to civilian life, Lugosi became an actor in Hungarian silent films, appearing in many of them under the stage name "Arisztid Olt".

Due to his activism in the actors' union in Hungary during the revolution of 1919 and his active participation in the Hungarian Soviet Republic,[12] he was forced to flee his homeland when the government changed hands, initially accompanied by his first wife Ilona Szmik.[13][4] They escaped to Vienna before settling in Berlin (in the Langestrasse), where he began acting in German silent films. During these moves, Ilona lost her unborn child,[14] after which she left Lugosi and returned home to her parents where she filed for divorce, and soon after remarried.[4]

Lugosi eventually travelled to New Orleans, Louisiana, in December 1920 working as a crewman aboard a merchant ship, then made his way north to New York City, where he again took up acting in (and sometimes directing) stage plays in 1921–1922, then worked in the New York silent film industry from 1923 to 1926. In 1921, he met and married his second wife, Ilona von Montagh, a young Hungarian emigree and stage actress whom he had worked with years before in Europe. They only lived together for a few weeks, but their divorce took until October 1925 to be finalized.[15]

He later moved to California in 1928 to tour in the Dracula stage play, and his Hollywood film career took off. Lugosi claimed he performed the Dracula play around 1,000 times during his lifetime. He eventually became a U.S. citizen in 1931, soon after the release of his film version of Dracula.[13][4]

Career

[edit]Early films

[edit]

Lugosi's first film appearance was in the 1917 Hungarian silent film Leoni Leo.[2] When appearing in Hungarian silent films, he mostly used the stage name Arisztid Olt.[16] Lugosi made at least 10 films in Hungary between 1917 and 1918 before leaving for Germany. Following the collapse of Béla Kun's Hungarian Soviet Republic in 1919, leftists and trade unionists became vulnerable, some being imprisoned or executed in public. Lugosi was proscribed from acting due to his participation in the formation of an actors' union. Exiled in Weimar-era Germany, he co-starred in at least 14 German silent films in 1920, among them Hypnose: Sklaven fremden Willens (1920), Der Januskopf (1920) and an adaptation of the Karl May novel Caravan of Death (1920).

Lugosi left Germany in October 1920, emigrating by ship to the United States, and entered the country at New Orleans in December 1920. He made his way to New York and was inspected by immigration officers at Ellis Island in March 1921.[17] He only declared his intention to become a US citizen in 1928; on June 26, 1931, he was naturalized.[18]

On his arrival in America, the 6-foot-1-inch (1.85 m),[16] 180-pound (82 kg) Lugosi worked for some time as a laborer, and then entered the theater in New York City's Hungarian immigrant colony. With fellow expatriate Hungarian actors he formed a small stock company that toured Eastern cities, playing for immigrant audiences. Lugosi acted in several Hungarian language plays before starring in his first English Broadway play, The Red Poppy in 1922.[19] Three more parts came in 1925–26, including a five-month run in the comedy-fantasy The Devil in the Cheese.[20] In 1925, he played an Arab Sheik in Arabesque which premiered in Buffalo, New York at the Teck Theatre before moving to Broadway.[21]

His first American film role was in the silent melodrama The Silent Command (1923) which was filmed in New York. Four other silent roles followed, villains and continental types, all in productions made in the New York area.[22] A rumor has circulated for decades among film historians that Lugosi played an uncredited bit part as a clown in the first film produced by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, He Who Gets Slapped (1924) starring Lon Chaney, but this has been heavily disputed. The rumor originated from the discovery of a publicity still from this film found posthumously in Lugosi's scrapbook, which showed an unidentified clown in heavy makeup standing near Lon Chaney in one scene. It was thought to be evidence that Lugosi appeared in the film, but historians all agree that is very unlikely, since Lugosi was in both Chicago (appearing in a play called The Werewolf) and New York at the time that film was in production in Hollywood.[23]

Dracula

[edit]

Lugosi was approached in the summer of 1927 to star in a Broadway theatre production of Dracula, which had been adapted by Hamilton Deane and John L. Balderston from Bram Stoker's 1897 novel.[24] The Horace Liveright production was successful, running in New York City for 261 performances before touring the United States to much fanfare and critical acclaim throughout 1928 and 1929. In 1928, Lugosi decided to stay in California when the play ended its first West Coast run. His performance had piqued the interest of Fox Film, and he was cast in the Hollywood studio's silent film The Veiled Woman (1929). He also appeared in the film Prisoners (also 1929), believed lost, which was released in both a silent and partial talkie version.[25]

In 1929, with no other film roles in sight, he returned to the stage as Dracula for a short West Coast tour of the play. Lugosi remained in California where he resumed his film work under contract with Fox, appearing in early talkies often as a heavy or an "exotic sheik". He also continued to lobby for his prized role in the film version of Dracula.[26]

Despite his critically acclaimed performance on stage, Lugosi was not Universal Pictures' first choice for the role of Dracula when the company optioned the rights to the Deane play and began production in 1930.[a] Different prominent actors, such as Paul Muni, Chester Morris, Ian Keith, John Wray, Joseph Schildkraut, Arthur Edmund Carewe, William Courtenay, John Carradine, and Conrad Veidt were considered. Lew Ayres was eventually hired to play Jonathan Harker, only to be replaced by Robert Ames after being cast in a different role in a different Universal Pictures film. Ames was in turn replaced with David Manners.[27] Lugosi had played the role on Broadway,[28] and was considered before director Tod Browning cast him in the role. The film was a major hit, but Lugosi was paid a salary of only $3,500, since he had too eagerly accepted the role.[13][29]

Typecasting

[edit]

Through his association with Dracula (in which he appeared with minimal makeup, using his natural, heavily accented voice), Lugosi found himself typecast as a horror villain in films such as Murders in the Rue Morgue (1932), The Black Cat (1934) and The Raven (1935) for Universal, and the independent White Zombie (1932). His accent, while a part of his image, limited the type of role he could play.[citation needed]

Lugosi did attempt to break type by auditioning for other roles. He lost out to Lionel Barrymore for the role of Grigori Rasputin in Rasputin and the Empress (also 1932); C. Henry Gordon for the role of Surat Khan in Charge of the Light Brigade (1936), and Basil Rathbone for the role of Commissar Dimitri Gorotchenko in Tovarich (1937), a role Lugosi had played on stage.[30] He played the elegant, somewhat hot-tempered General Nicholas Strenovsky-Petronovich in International House (1933).[citation needed]

Regardless of controversy, five films at Universal – The Black Cat (1934), The Raven (1935), The Invisible Ray (1936), Son of Frankenstein (1939), Black Friday (1940), plus minor cameo performances in Gift of Gab (1934) and two at RKO Pictures, You'll Find Out (1940) and The Body Snatcher (1945) – paired Lugosi with Boris Karloff. Despite the relative size of their roles, Lugosi inevitably received second billing, below Karloff. There are contradictory reports of Lugosi's attitude toward Karloff, some claiming that he was openly resentful of Karloff's long-term success and ability to gain good roles beyond the horror arena, while others suggested the two actors were – for a time, at least – amicable. Karloff himself in interviews suggested that Lugosi was initially mistrustful of him when they acted together, believing that the Englishman would attempt to upstage him. When this proved not to be the case, according to Karloff, Lugosi settled down and they worked together amicably (though some have further commented that the English Karloff's on-set demand to break from filming for mid-afternoon tea annoyed Lugosi).[31] Lugosi did get a few heroic leads, as in Universal's The Black Cat after Karloff had been accorded the more colorful role of the villain, The Invisible Ray, and a romantic role in producer Sol Lesser's adventure serial The Return of Chandu (1934), but his typecasting problem appears to have been too entrenched to be alleviated by those films.[citation needed]

Lugosi addressed his plea to be cast in non-horror roles directly to casting directors through his listing in the 1937 Players Directory, published by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, in which he (or his agent) calls the idea that he is only fit for horror films "an error."[32]

Career decline

[edit]Lugosi developed severe, chronic sciatica, ostensibly aggravated by injuries received during his military service. Though at first he was treated with benign pain remedies such as asparagus juice, doctors increased the medication to opiates. The growth of his dependence on opiates, particularly morphine and (after 1947, when it became available in America) methadone, was directly proportional to the dwindling of Lugosi's screen offers. The problem first manifested itself in 1937, when Lugosi was forced to withdraw from a leading role in a serial production, The Secret of Treasure Island,[33] due to constant back pain.

Historian John McElwee reports, in his 2013 book Showmen, Sell It Hot!, that Bela Lugosi's popularity received a much-needed boost in August 1938, when California theater owner Emil Umann revived Dracula and Frankenstein as a special double feature. The combination was so successful that Umann scheduled extra shows to accommodate the capacity crowds, and invited Lugosi to appear in person, which thrilled new audiences that had never seen Lugosi's classic performance. "I owe it all to that little man at the Regina Theatre," said Lugosi of exhibitor Umann. "I was dead, and he brought me back to life."[34] Universal took notice of the tremendous business and launched its own national re-release of the same two horror favorites. The studio then rehired Lugosi to star in new films, fortunately just as Lugosi's fourth wife had given birth to a son.

Universal cast Lugosi in Son of Frankenstein (1939), appearing in the character role of Ygor, a mad blacksmith with a broken neck, in heavy makeup and beard. Lugosi was third-billed with his name above the title alongside Basil Rathbone as Dr. Frankenstein's son and Boris Karloff reprising his role as Frankenstein's monster. Regarding Son of Frankenstein, the film's director Rowland V. Lee said his crew let Lugosi "work on the characterization; the interpretation he gave us was imaginative and totally unexpected ... when we finished shooting, there was no doubt in anyone's mind that he stole the show. Karloff's monster was weak by comparison."[35]

The same year saw Lugosi making a rare appearance in an A-list motion picture: he was a stern Soviet commissar in the Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer romantic comedy Ninotchka, starring Greta Garbo and directed by Ernst Lubitsch. Lugosi was quite effective in this small but prestigious character part and even received top billing among the film's supporting cast, all of whom had significantly larger roles. It might have been a turning point for the actor, but within the year he was back on Hollywood's Poverty Row, playing leads for Sam Katzman; the producer was then releasing through Monogram Pictures. At Universal, Bela Lugosi was usually cast for his name value; he often received star billing for what amounted to a supporting part.

Lugosi went to 20th Century-Fox for The Gorilla (1939), which had him playing straight man (a butler) to Patsy Kelly and the Ritz Brothers. When Lugosi's Black Friday premiered in 1940 on a double bill with the Vincent Price film The House of the Seven Gables, Lugosi and Price both appeared in person at the Chicago Theatre where it opened on Feb. 29, 1940 and remained for four performances.[36] He was finally cast in the role of Frankenstein's monster for Universal's Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man (1943). (At the end of the previous film in the series, The Ghost of Frankenstein (1942), Lugosi's voice had been dubbed over that of Lon Chaney Jr. since Ygor's brain was now in the Monster's skull.[37]) But at the last minute, Lugosi's heavily accented dialogue was edited out after the film was completed, along with the idea of the Monster being blind, leaving his performance featuring groping, outstretched arms and moving lips seeming enigmatic (and funny) to audiences.

Lugosi kept busy during the 1940s as a screen menace. In addition to his nine Monogram features, he worked in three features for RKO and one for Columbia (The Return of the Vampire, 1943). He also accepted the lead in an experimental, economical feature, shot in the semi-professional 16mm film format and blown up to 35mm for theatrical release, Scared to Death (completed April 1946,[38] released June 1947). The feature is noteworthy as being Bela Lugosi's only color film.

Lugosi played Dracula for a second and final time on film in Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein (1948), which was his last "A" movie. For the remainder of his life, he appeared – less and less frequently – in obscure, forgettable, low-budget B features. From 1947 to 1950, he performed in summer stock, often in productions of Dracula or Arsenic and Old Lace, and during the rest of the year, made personal appearances in a touring "spook show", and on early commercial television.

In September 1949, Milton Berle invited Lugosi to appear in a sketch on Texaco Star Theatre.[39] Lugosi memorized the script for the skit, but became confused on the air when Berle began to ad lib.[40] He also appeared on the anthology series Suspense on October 11, 1949, in a live adaptation of Edgar Allan Poe's "The Cask of Amontillado".[41]

In 1951, while in England to play a six-month tour of Dracula, Lugosi co-starred in a lowbrow film comedy, Mother Riley Meets the Vampire (also known as Vampire Over London and My Son, the Vampire), released the following year. Following his return to the United States, he was interviewed for television, and reflected wistfully on his typecasting in horror parts: "Now I am the boogie man". In the same interview, he expressed a desire to play more comedy, as he had in the Mother Riley farce. Independent producer Jack Broder took Lugosi at his word, casting him in a jungle-themed comedy, Bela Lugosi Meets a Brooklyn Gorilla (1952), starring nightclub comedians Duke Mitchell and Jerry Lewis look-alike Sammy Petrillo, whose act closely resembled that of Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis (Martin and Lewis). Hal B. Wallis, Martin and Lewis's producer, unsuccessfully sued Broder.

Stage and personal appearances

[edit]Lugosi enjoyed a lively career on stage, with plenty of personal appearances. As film offers declined, he became more and more dependent on live venues to support his family. Lugosi took over the role of Jonathan Brewster from Boris Karloff for Arsenic and Old Lace. Lugosi had also expressed interest in playing Elwood P. Dowd in Harvey to help himself professionally. He also made plenty of personal live appearances to promote his horror image or an accompanying film.[30][42]

The Vincent Price film, House of Wax premiered in Los Angeles at the Paramount Theatre on April 16, 1953. The film played at midnight with a number of celebrities in the audience that night (Judy Garland, Ginger Rogers, Rock Hudson, Broderick Crawford, Gracie Allen, Eddie Cantor, Shelley Winters and others). Producer Alex Gordon, knowing Lugosi was in dire need of cash, arranged for the actor to stand outside the theater wearing a cape and dark glasses, holding a man costumed as a gorilla on a leash. He later allowed himself to be photographed drinking a glass of milk at a Red Cross booth there. When Lugosi playfully attempted to bite the "nurse" in attendance, she overreacted and spilled a glass of milk all over his shirt and cape. Afterward, Lugosi was interviewed by a reporter who botched the interview by asking the prearranged questions out of order, thoroughly confusing the aging star. Embarrassed, Lugosi left abruptly, without attending the screening.[43]

Ed Wood and final projects

[edit]

Late in his life, Bela Lugosi again received star billing in films when the ambitious but financially limited filmmaker Ed Wood, a fan of Lugosi, found him living in obscurity and near-poverty and offered him roles in his films, such as an anonymous narrator in Glen or Glenda (1953) and a mad scientist in Bride of the Monster (1955). During post-production of the latter, Lugosi decided to seek treatment for his drug addiction, and the film's premiere was arranged to raise money for Lugosi's hospital expenses (resulting in a paltry amount of money). According to Kitty Kelley's biography of Frank Sinatra, when the entertainer heard of Lugosi's problems, he visited Lugosi at the hospital and gave him a $1,000 check. Sinatra would recall Lugosi's amazement at his visit, since the two men had never met before.[44]

During an impromptu interview upon his release from the treatment center in 1955, Lugosi stated that he was about to begin work on a new Ed Wood film called The Ghoul Goes West. This was one of several projects proposed by Wood, including The Phantom Ghoul and Dr. Acula. With Lugosi in his Dracula cape, Wood shot impromptu test footage, with no particular storyline in mind, in front of Tor Johnson's home, at a suburban graveyard, and in front of Lugosi's apartment building on Carlton Way. This footage ended up posthumously in Wood's Plan 9 from Outer Space (1957[45]), which was filmed in 1956 soon after Lugosi died. Wood hired Tom Mason, his wife's chiropractor, to double for Lugosi in additional shots.[46] Mason was noticeably taller and thinner than Lugosi, and had the lower half of his face covered with his cape in every shot, as Lugosi sometimes did in Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein.

Following his treatment, Lugosi made one final film, in late 1955, The Black Sleep, for Bel-Air Pictures, which was released in the summer of 1956 through United Artists with a promotional campaign that included several personal appearances by Lugosi and his co-stars, as well as Maila Nurmi (TV's horror host "Vampira"). To Lugosi's disappointment, however, his role in this film was that of a mute butler with no dialogue. Lugosi was intoxicated and very ill during the film's promotional campaign and had to return to L.A. earlier than planned. He never got to see the finished film. Tor Johnson said in interviews that Lugosi kept screaming that he wanted to die the night they shared a hotel room together.[47]

In 1959, a British film called Lock Up Your Daughters was theatrically released (in the U.K.), composed of clips from Bela Lugosi's Monogram pictures from the 1940s. The film is lost today, but a March 16, 1959, critical review in the Kinematograph Weekly mentioned that the movie contained new Lugosi footage (intriguing since Lugosi had died in 1956). Back in 1950 however, Lugosi had appeared on a one-hour TV program called Murder and Bela Lugosi (which WPIX-TV broadcast on Sept. 18, 1950) in which Lugosi was interviewed and provided commentary about a number of his old horror films while clips from the films were being shown; historian Gary Rhodes thinks some of this Lugosi TV production found its way into the 1959 British film, which would finally explain the mystery.[48][49]

Personal life

[edit]

Lugosi repeatedly married. In June 1917, Lugosi married 19-year-old Ilona Szmik (1898–1991) in Hungary.[50] The couple divorced after Lugosi was forced to flee his homeland for political reasons (risking execution if he stayed) and Ilona did not wish to leave her parents. The divorce became final on July 17, 1920, and was uncontested as Lugosi could not show up for the proceedings.[3] (Szmik then married wealthy Hungarian architect Imre Francsek in December 1920, moved with him to Iran in 1930, had two children, and died in 1991.)[51]

After living briefly in Germany, Lugosi left Europe by ship and arrived in New Orleans on October 27, 1920, and, after making his way north, underwent his primary alien inspection at Ellis Island, N.Y. on March 23, 1921.

In September 1921, he married Hungarian actress Ilona von Montagh in New York City, and she filed for divorce on November 11, 1924, charging him with adultery and complaining that he wanted her to abandon her acting career to keep house for him.[52] The divorce became final in October, 1925. (Lugosi learned in 1935 that von Montagh and a female friend were both arrested for shoplifting in New York City, which was the last he heard of her.).[53]

Lugosi took his place in Hollywood society and scandal when he married wealthy San Francisco resident Beatrice Woodruff Weeks (1897–1931), widow of architect Charles Peter Weeks, on July 27, 1929. Weeks subsequently filed for divorce on November 4, 1929, accusing Lugosi of infidelity, citing actress Clara Bow as the "other woman", and claimed Lugosi tried to take her checkbook and the key to her safe deposit box away from her. She even claimed he slapped her in the face one night because she ate a pork chop he had hidden in their refrigerator. Lugosi complained of her excessive drinking and dancing with other men at social gatherings. The divorce became official on December 9, 1929. (Weeks died 17 months later (at age 34) from alcoholism in Panama, Lugosi never receiving a penny from her fortune.)

On June 26, 1931, Lugosi became a naturalized United States citizen.[50]

In 1933, the 51-year-old Lugosi married 22-year-old Lillian Arch (1911–1981), the daughter of Hungarian immigrants living in Hollywood. Lillian's father was against her marriage to Lugosi at first as the actor was experiencing financial difficulties at the time, so Bela talked her into eloping with him to Las Vegas in January 1933.[54] They remained married for 20 years and they had a child, Bela G. Lugosi, in 1938. (Bela eventually had four grandchildren (Greg, Jeff, Tim, and Lynne) and seven great-grandchildren,[55] although he did not live long enough to meet any of them.)[56]

Lillian and Bela vacationed on their lakeshore property in Lake Elsinore, California (then called Elsinore), on several lots between 1944 and 1953. Lillian's parents lived on one of their properties, and Lugosi frequented the health spa there. Bela Lugosi Jr. was boarded at the Elsinore Naval and Military School in Lake Elsinore, and also lived with Lillian's parents while she and Bela were touring.

After almost breaking up their marriage in 1944, Lillian and Bela finally divorced on July 17, 1953,[57] at least partially because of Bela's excessive drinking[2] and his jealousy over Lillian taking a full-time job as an assistant to actor Brian Donlevy on Donlevy's radio and television series Dangerous Assignment. Lillian obtained custody of their son Bela Jr.[58] Lugosi called the police one night after Lillian left him and threatened to commit suicide, but when the police showed up at his apartment, he denied making the call.[59](Lillian eventually did marry Brian Donlevy in 1966, by which time he had also become an alcoholic, and she died in 1981.)[60]

Lugosi married Hope Lininger, his fifth wife, in 1955; she was 37 years his junior. She had been a fan, writing letters to him when he was in the hospital recovering from his drug addiction. She would sign her letters "A dash of Hope". They remained married until his death in 1956. However Bela and Hope were actually discussing getting divorced before he died.[61]

Death

[edit]

Lugosi died of a heart attack on August 16, 1956, in the bedroom of his Los Angeles apartment while taking a nap. His wife, Hope, discovered him when she came home from work that evening, his apparently having died peacefully in his sleep around 6:45 p.m. according to the medical examiner[2] at the age of 73.[1] The rumor that Lugosi was clutching the script for The Final Curtain, a planned Ed Wood project, at the time of his death is not true.[62]

Lugosi was buried wearing one of the "Dracula" capes and his full costume as well as his Dracula ring in the Holy Cross Cemetery in Culver City, California. Contrary to popular belief, Lugosi never requested to be buried in his cloak; Bela G. Lugosi confirmed on numerous occasions that he and his mother, Lillian, made the decision but believed that it is what his father would have wanted.[63]

The funeral was held on Saturday, August 18 at the Utter-McKinley funeral home in Hollywood. Attendees in addition to immediate family included former wife of 20 years Lillian, Forrest J. Ackerman, Ed Wood (pall bearer), Tor Johnson, Conrad Brooks, Richard Sheffield, Norma McCarty, Loretta King, Paul Marco and actor George Becwar. Bela's fourth wife Lillian paid for the cemetery plot and stone (which was inscribed "Beloved Father"), while Hope Lugosi paid for the coffin and the funeral service. Lugosi's will left several inexpensive pieces of real estate in Elsinore and only $1,000 cash to his son, but since the will had been written on Jan. 12, 1954 (before Lugosi's fifth marriage), Bela Jr. had to share the thousand dollars evenly with Hope Lugosi.

Hope later gave most of Lugosi's personal belongings and memorabilia to Bela's young neighborhood friend Richard Sheffield, who gave Lugosi's duplicate Dracula cape to Bela Jr. and sold some of the other items to Forrest J. Ackerman. Hope told Sheffield she had searched the apartment for several days looking for $3,000 she suspected Lugosi had hidden there, but she never found it. Sheffield said years later "Lugosi had probably spent it all on alcohol." Hope later moved to Hawaii, where she worked for many years as a caregiver in a leper colony.[64][65] Hope died in Hawaii in 1997, at age 78, having never remarried. Before her death, she gave several interviews to the fan press.[66]

California Supreme Court decision on personality rights

[edit]In 1979, the Lugosi v. Universal Pictures decision by the California Supreme Court held that Lugosi's personality rights could not pass to his heirs, as a copyright would have. The court ruled that under California law, any rights of publicity, including the right to his image, terminated with Lugosi's death.[b] Six years later the law was changed by the California Celebrities Rights Act.

Legacy

[edit]The cape Lugosi wore in Dracula (1931) was in the possession of his son until it was put up for auction in 2011. It was expected to sell for up to $2 million,[68] but has since been listed again by Bonhams in 2018.[69] In 2019, the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures announced acquisition of the cape via partial donation from the Lugosi family.[70] In 2019 it was announced that the cape would be on display the following year.[71]

Andy Warhol's 1963 silkscreen The Kiss depicts Lugosi from Dracula about to bite into the neck of co-star Helen Chandler, who played Mina Harker. A copy sold for $798,000 at Christie's in May 2000.[72]

Lugosi was given a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame in 1960. His star is mentioned in "Celluloid Heroes", a song performed by The Kinks and written by their lead vocalist and principal songwriter, Ray Davies. It appeared on their 1972 album Everybody's in Show-Biz.[73]

In 1979, a song called "Bela Lugosi's Dead" was released by UK post-punk band Bauhaus and is a pioneering song in the gothic rock genre. On choosing the topic of the song, the band's bassist David J remarked "There was a season of old horror films on TV and I was telling Daniel about how much I loved them. The one that had been on the night before was Dracula [1931]. I was saying how Bela Lugosi was the quintessential Dracula, the elegant depiction of the character."[74]

An episode of Sledge Hammer! titled "Last of the Red Hot Vampires" was an homage to Bela Lugosi; at the end of the episode, it was dedicated to "Mr. Blasko".[75]

Bela Lugosi and Boris Karloff are referenced in the Curtis Stigers' song "Sleeping with the Lights On", from the 1991 album Curtis Stigers.

In Tim Burton's Ed Wood, Bela Lugosi is portrayed by Martin Landau, who received the 1994 Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor for the performance. According to Bela G. Lugosi (his son), Forrest Ackerman, Dolores Fuller and Richard Sheffield, the film's portrayal of Lugosi is inaccurate: In real life, he never used profanity, did not hate Karloff, owned no small dogs, nor did he sleep in a coffin. Also Ed Wood did not meet Lugosi in a funeral parlor, but rather through his roommate Alex Gordon.[47][76]

Péter Müller's 1998 theatrical play Lugosi – the Shadow of the Vampire (Hungarian: Lugosi – a vámpír árnyéka) is based on Lugosi's life, telling the story of his life as he became typecast as Dracula and as his drug addiction worsened.[77] In the Hungarian production, directed by István Szabó, Lugosi was played by Ivan Darvas.[78][79]

In 2001, BBC Radio 4 broadcast There Are Such Things by Steven McNicoll and Mark McDonnell. Focusing on Lugosi and his well-documented struggle to escape from the role that had typecast him, the play went on to receive the Hamilton Deane Award for best dramatic presentation from the Dracula Society in 2002.[80]

On July 19, 2003, German artist Hartmut Zech erected a bust of Lugosi on one of the corners of Vajdahunyad Castle in Budapest.[81][82]

The Ellis Island Immigration Museum in New York City features a live 30-minute play that focuses on Lugosi's illegal entry into the country via New Orleans and his arrival at Ellis Island months later to enter the country legally.[83]

In 2013 the Hungarian electronic music band Žagar recorded a song entitled "Mr. Lugosi", which contains a recording of the voice of Bela Lugosi. The song was a part of the Light Leaks record.[84]

According to Paru Itagaki, the creator of the Japanese manga/anime Beastars, the main character Legoshi was inspired by Bela Lugosi (regarding the similar-sounding names).[85]

In 2020, Legendary Comics published an adaptation of Bram Stoker's 1897 Dracula novel, which used the likeness of Lugosi.[86]

A 2021 hardcover graphic novel depicting the life of Bela Lugosi was written and drawn by Koren Shadmi, entitled Lugosi: The Rise and Fall of Hollywood's Dracula.[87]

Notes

[edit]- ^ A persistent rumor asserts that director Tod Browning's long-time collaborator Lon Chaney was Universal's first choice for the role, and that Lugosi was chosen only due to Chaney's death from cancer shortly before production. While there is no question that Chaney would be anyone's first choice, Chaney had been under long-term contract to Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer since 1925, and had negotiated a lucrative new contract just before his death.[citation needed] Chaney and Browning had worked together on several projects (including four of Chaney's final five releases), but Browning was only a last-minute choice to direct the movie version of Dracula after the death of director Paul Leni, who had originally been slated to direct.

- ^ California's descendibility statute for rights of publicity, Civil Code Section 990, was enacted in 1988, and Lugosi's estate now licenses the commercial use of his name and image. The right of publicity in some states endures for 50, 70, 75 or 100 years past the death of the celebrity.[67]

References

[edit]- ^ a b "From the Archives: Actor Bela Lugosi, Dracula of Screen, Succumbs After Heart Attack at 73". Los Angeles Times. August 17, 1956. Retrieved December 31, 2016.

- ^ a b c d Bela Lugosi: Dreams and Nightmares by Gary D. Rhodes, with Richard Sheffield, (2007) Collectables/Alpha Video Publishers, ISBN 0977379817 (hardcover)

- ^ a b c Arthur Lennig, The Immortal Count, University Press of Kentucky, 2003, p. 21; ISBN 978-0813122731.

- ^ a b c d e f g Milano, Roy (2006). Osborn, Jennifer (ed.). Monsters: A Celebration of the Classics from Universal Studios. New York: Del Ray Books, imprint of Random House, Inc. p. 38. ISBN 0345486854. Referenced information is from an essay in the book written by his son Bela G. Lugosi.

- ^ Rhodes, Gary (1997). Lugosi: His Life in Films, on Stage, and in the Hearts of Horror Lovers. ISBN 0786402571.

- ^ "United States Census, 1930", database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:XCJB-Z61 : accessed May 20, 2018), Bela Lugosi, Los Angeles (Districts 0001-0250), Los Angeles, California, United States; citing enumeration district (ED) ED 47, sheet 9A, line 4, family 193, NARA microfilm publication T626 (Washington D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 2002), roll 133; FHL microfilm 2,339,868.

- ^ Rhodes, Gary (1997). Lugosi: His Life in Films, on Stage, and in the Hearts of Horror Lovers. McFarland. ISBN 0786402571.

- ^ a b Arthur Lennig, The Immortal Count, University Press of Kentucky, 2003, p. 21; ISBN 978-0813122731.

- ^ "15 Intriguing Halloween-Related Factoids!". Huffington Post. November 3, 2011.

- ^ Arthur Lennig, The Immortal Count, University Press of Kentucky, 2003, pp. 25–26, 28–29; ISBN 978-0813122731.

- ^ "Drakula a lövészárokban – így harcolt Lugosi Béla az első világháborúban". October 24, 2018.

- ^ Kuhlenbeck, Mike (March 5, 2019). "Béla Lugosi: actor, union leader, anti-fascist". Workers World. Retrieved March 23, 2021.

- ^ a b c Lugosi: The Man Behind the Cape by Robert Cremer (1976) ISBN 0809281376 (hardcover)

- ^ Bela Lugosi: Dreams and Nightmares by Gary D. Rhodes, with Richard Sheffield, (2007) Collectables/Alpha Video Publishers. pg. 58. ISBN 0977379817 (hardcover)

- ^ Bela Lugosi: Dreams and Nightmares by Gary D. Rhodes, with Richard Sheffield, (2007) Collectables/Alpha Video Publishers. pg. 61. ISBN 0977379817 (hardcover)

- ^ a b Mank, Gregory W. (2009). Bela Lugosi and Boris Karloff : the expanded story of a haunting collaboration, with a complete filmography of their films together. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Co., Publishers. pp. 22–23. ISBN 978-0786434800. OCLC 607553826.

- ^ Passenger list of the S.S. Graf Tisza Istvan, port of New Orleans, December 4, 1920, with later notation.

- ^ Ancestry.com. Selected U.S. Naturalization Records – Original Documents, 1790–1974 (World Archives Project) [database on-line]. Provo, Utah, US: The Generations Network, Inc., 2009.

- ^ Skal, David (2004). Hollywood Gothic. New York City: Faber and Faber Inc. p. 124. ISBN 978-0571211586.

- ^ Bela Lugosi profile, ibdb.com; accessed November 1, 2015.

- ^ Bela Lugosi premieres in Buffalo, New York

- ^ "Bela Lugosi – The Official Site". Retrieved February 4, 2020.

- ^ Lugosi: The Man Behind the Cape by Robert Cremer (1976) ISBN 0809281376

- ^ Rhodes, Gary Don (1997). "Stage Appearances" (Google Books). Lugosi: his life in films, on stage, and in the hearts of horror lovers. McFarland. p. 169. ISBN 978-0786402571. Retrieved February 18, 2009.

- ^ Lennig, Arthur (2010). The Immortal Count: The Life and Films of Bela Lugosil. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0813126616.

- ^ "Why Bela Lugosi remains the ultimate Dracula". faroutmagazine.co.uk. October 20, 2020. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ "Dracula". catalog.afi.com. Archived from the original on December 2, 2021. Retrieved December 2, 2021.

- ^ Hoberman, J. (October 24, 2014). "'Universal Classic Monsters' Puts Horror on Parade". The New York Times. Retrieved January 16, 2020.

- ^ "12 Surprising Facts About Bela Lugosi". August 16, 2016. Retrieved August 4, 2017.

- ^ a b Kaffenberger, Bill; Rhodes, Gary (2015). Bela Lugosi In Person. BearManor Media. ISBN 978-1593938055.

- ^ Mank, Gregory William (2009). Bela Lugosi and Boris Karloff : the expanded story of a haunting collaboration, with a complete filmography of their films together. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Co., Publishers. pp. 237–238. ISBN 978-0786434800.

- ^ Michael Mallory. Universal Studios Monsters: A Legacy of Horror, 2009, Universe, p. 63. ISBN 978-0789318961.

- ^ Hollywood Reporter, "[Walter] Miller Goes In Lugosi Part In Columbia 'Island'", Jan. 29, 1938, p. 5.

- ^ John McElwee, Showmen, Sell It Hot!, GoodKnight, 2013, p. 58.

- ^ Edwards, Phil (January 1997). "Son of Frankenstein". Starburst. Vol. 3, no. 10. Marvel UK. ISBN 0786402571.

- ^ Bela Lugosi: Dreams and Nightmares by Gary D. Rhodes, with Richard Sheffield, (2007) Collectables/Alpha Video Publishers. pg. 103. ISBN 0977379817 (hardcover)

- ^ "Bela Lugosi | Hungarian-American actor". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved August 4, 2017.

- ^ Edith Gwynn, Hollywood Reporter, Apr. 3, 1946, p. 2.

- ^ Star Theater Episode Guide Archived May 17, 2020, at the Wayback Machine, tv.com; accessed November 1, 2015.

- ^ Weaver, Tom (2004). Science Fiction and Fantasy Film Flashbacks: Conversations with 24 Actors, Writers, Producers and Directors from the Golden Age. McFarland. p. 160. ISBN 0786420707.

- ^ The Complete Actors' Television Credits, 1948–1988, James Robert Parrish and Vincent Terrace [ISBN missing][page needed]

- ^ Kaffenberger, Bill; Rhodes, Gary (2012). No Traveler Returns: The Lost Years of Bela Lugosi. BearManor Media. ISBN 978-1593932855.

- ^ Gary Don Rhodes (1997). Lugosi. His Life in Films, on Stage, and in the Hearts of Horror Lovers. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. p. 198. ISBN 978-0786402571.

- ^ Kelley, Kitty (1987). His Way: The Unauthorized Biography of Frank Sinatra. Bantam Books. p. 248. ISBN 0553265156.

- ^ Rudolph Grey, Nightmare of Ecstasy: The Life and Art of Edward D. Wood, Jr. (1992). p. 203. ISBN 978-0922915248.

- ^ Nuzum, Eric. "Bela Lugosi's Legacy". Lost. Archived from the original on September 17, 2008. Retrieved October 8, 2008.

- ^ a b Rhodes, Gary; Sheffield, Richard (2007). Bela Lugosi: Dreams and Nightmares. Collectables Press. ISBN 978-0977379811.

- ^ "Filmography – Bela Lugosi – the Official Site".

- ^ Review of "Lock Up Your Daughters". Kinematograph Weekly. March 16, 1959

- ^ a b Arthur Lennig, The Immortal Count, University Press of Kentucky, 2003, p. 68; ISBN 978-0813122731.

- ^ Bela Lugosi: Dreams and Nightmares by Gary D. Rhodes, with Richard Sheffield, (2007) Collectables/Alpha Video Publishers. pg. 59. ISBN 0977379817 (hardcover)

- ^ Arthur Lennig, The Immortal Count, University Press of Kentucky, 2003, ISBN 978-0813122731.

- ^ Bela Lugosi: Dreams and Nightmares by Gary D. Rhodes, with Richard Sheffield, (2007) Collectables/Alpha Video Publishers. Pg 61. ISBN 0977379817

- ^ Bela Lugosi: Dreams and Nightmares by Gary D. Rhodes, with Richard Sheffield, (2007) Collectables/Alpha Video Publishers. pg. 71. ISBN 0977379817 (hardcover)

- ^ "Nancy Marie Lugosi, Obituary". La Cañada Flintridge Outlook Valley Sun. Outlook Newspapers. 3 September 1938. Retrieved 2022-11-10.

- ^ "Friedemann O'Brien Goldberg & Zarian Names Bela G. Lugosi Of Counsel". Metropolitan News-Enterprise. Retrieved April 20, 2008.

- ^ "Divorced". Time. July 27, 1953. Archived from the original on March 30, 2008. Retrieved March 21, 2008.

- ^ Arthur Lennig, The Immortal Count, University Press of Kentucky, 2003, p. 393; ISBN 978-0813122731.

- ^ Bela Lugosi: Dreams and Nightmares by Gary D. Rhodes, with Richard Sheffield, (2007) Collectables/Alpha Video Publishers. Pg. 70. ISBN 0977379817

- ^ "Beyond Quatermass – Brian Donlevy, the Good Bad Guy: A Bio-Filmography by Derek Sculthorpe". Filmint.nu. February 7, 2019.

- ^ No Traveler Returns: The Lost Years of Bela Lugosi, Bill Kaffenberger and Gary D. Rhodes (2012). Last chapter. BearManor Media, ISBN 1593932855

- ^ Rhodes, Gary Don (1997). Lugosi: His Life in Films, on Stage, and in the Hearts of Horror Lovers. McFarland. p. 36. ISBN 0786402571.

- ^ Bela G. Lugosi states this in "The Road to Dracula", a documentary supplement in the DVD "Dracula -(1931)" [Universal Studios Classic Monster Collection, Universal DVD #903 249 9.11]

- ^ Bela Lugosi: Dreams and Nightmares by Gary D. Rhodes, with Richard Sheffield, (2007) Collectables/Alpha Video Publishers, ISBN 0977379817 pp. 258–264.

- ^ Arthur Lennig, The Immortal Count, University Press of Kentucky, 2003 ISBN 978-0813122731.

- ^ Arthur Lennig, The Immortal Count, University Press of Kentucky, 2003 ISBN 978-0813122731.

- ^ "Lugosi v. Universal Pictures, 603 P.2d 425 (Cal. 1979)". FindLaw. Archived from the original on March 9, 2007. Retrieved February 14, 2007.

In this decision preceding (and precipitating) the Legislature's enactment of Section 990, the California Supreme Court held that rights of publicity were not descendible in California. Bela Lugosi's heirs, Hope Lininger Lugosi and Bela George Lugosi, sued to enjoin and recover profits from Universal Pictures for licensing Lugosi's name and image on merchandise reprising Lugosi's title role in the 1931 film Dracula. The California Supreme Court faced the question whether Bela Lugosi's film contracts with Universal included a grant of merchandising rights in his portrayal of Count Dracula, and the descendibility of any such rights. Adopting the opinion of Justice Roth for the Court of Appeal, Second Appellate District, the court held that the right to exploit one's name and likeness is personal to the artist and must be exercised, if at all, by him during his lifetime. Lugosi, 603 P.2d at 431.

- ^ "Bela Lugosi's 'Dracula' Cape To Be Auctioned Off". NPR. Retrieved May 24, 2019.

- ^ "Bonhams : Bela Lugosi's Count Dracula cape from Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein". www.bonhams.com. Retrieved November 18, 2019.

- ^ "Academy Museum of Motion Pictures Announces Acquisition of Bela Lugosi's Cape from Dracula". Oscars.org | Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. October 18, 2019. Retrieved November 18, 2019.

- ^ Squires, John (October 21, 2019). "Bela Lugosi's Screen-Worn 'Dracula' Cape Will Be on Display at the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures". Bloody Disgusting!. Retrieved November 18, 2019.

- ^ Andy Warhol (1928–1987): The Kiss (Bela Lugosi), christies.com; accessed November 1, 2015.

- ^ Palmer, Bob (October 26, 1972). "Everybody's in Showbiz". Rolling Stone. Wordpress.com VIP. Retrieved February 21, 2019.

- ^ Hughes, Rob (February 28, 2020). "Bauhaus on 'Bela Lugosi's Dead': "It was the 'Stairway To Heaven' of the 1980s"". Uncut. Retrieved September 22, 2021.

- ^ ""Sledge Hammer!" the Last of the Red Hot Vampires (TV Episode 1987) - IMDb". IMDb.

- ^ Rhodes, Gary; Weaver, Tom (2015). Ed Wood's Bride of the Monster. BearManor Media. ISBN 978-1593938574.[page needed]

- ^ "Die Bela Lugosi Story – Müller, Péter / Theobalt , Gerold / Schmidtke, Wolfgang". www.theatertexte.de. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- ^ Kővári, Orsolya (May 24, 2013). "Mr Dracula – On Bela Lugosi". Hungarian Review. IV (3). Translated by Péter Balikó Lengyel.

- ^ "Lugosi (Shadow of the Vampire)". Madách Színház. 2011. Archived from the original on August 5, 2020. Retrieved August 9, 2020.

- ^ "The Hamilton Deane Award". www.thedraculasociety.org.uk. Retrieved August 9, 2020.

- ^ "Hartmut Zech – Steinmetz- und Steinbildhauermeister". www.meisterzech.de. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- ^ "A Béla Lugosi Bust Was Snuck Onto the Facade of This Budapest Castle". Atlas Obscura. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- ^ "Visiting the Ellis Island Immigration Museum". ellisisland.org. Retrieved November 1, 2015.

- ^ ŽAGAR - Light Leaks bandcamp.com accessed December 3, 2022.

- ^ Santilli, Morgana (July 1, 2019). "Review: Can carnivore instinct be overcome in BEASTARS?". The Beat. Comics Culture. Retrieved November 8, 2021.

- ^ Evangelista, Chris (13 August 2020). "Bela Lugosi is Dracula Again in New Comic Arriving This October". /Film. Archived from the original on 25 December 2020.

- ^ "BN No Results Page".

Further reading

[edit]- Ed Wood's Bride of the Monster by Gary D. Rhodes and Tom Weaver (2015) BearManor Media, ISBN 1593938578

- Tod Browning's Dracula by Gary D. Rhodes (2015) Tomahawk Press, ISBN 0956683452

- Bela Lugosi In Person by Bill Kaffenberger and Gary D. Rhodes (2015) BearManor Media, ISBN 1593938055

- No Traveler Returns: The Lost Years of Bela Lugosi by Bill Kaffenberger and Gary D. Rhodes (2012) BearManor Media, ISBN 1593932855

- Bela Lugosi: Dreams and Nightmares by Gary D. Rhodes, with Richard Sheffield, (2007) Collectables/Alpha Video Publishers, ISBN 0977379817 (hardcover)

- Lugosi: His Life on Film, Stage, and in the Hearts of Horror Lovers by Gary D. Rhodes (2006) McFarland & Company, ISBN 978-0786427659

- The Immortal Count: The Life and Films of Bela Lugosi by Arthur Lennig (2003), ISBN 0813122732 (hardcover)

- Bela Lugosi (Midnight Marquee Actors Series) by Gary Svehla and Susan Svehla (1995) ISBN 1887664017 (paperback)

- Bela Lugosi: Master of the Macabre by Larry Edwards (1997), ISBN 188111709X (paperback)

- Films of Bela Lugosi by Richard Bojarski (1980) ISBN 0806507160 (hardcover)

- Sinister Serials of Boris Karloff, Bela Lugosi and Lon Chaney, Jr. by Leonard J. Kohl (2000) ISBN 1887664319 (paperback)

- Vampire over London: Bela Lugosi in Britain by Frank J. Dello Stritto and Andi Brooks (2000) ISBN 0970426909 (hardcover)

- Lugosi: The Man Behind the Cape by Robert Cremer (1976) ISBN 0809281376 (hardcover)

- Bela Lugosi: Biografia di una metamorfosi by Edgardo Franzosini (1998) ISBN 8845913708

- Lugosi: The Rise and Fall of Hollywood's Dracula by Koren Shadmi (Life Drawn graphic novel)(2021) ISBN 1643376616

External links

[edit]- Official website

- https://www.retroagogo.com/categories/collections/bela-lugosi/

- Bela Lugosi at IMDb

- Bela Lugosi at PORT.hu (in Hungarian)

- Bela Lugosi at AllMovie

- Bela Lugosi at the Internet Broadway Database

- Video Biography at CinemaScream.com

- How to pronounce Bela Lugosi? on YouTube

- A Tribute to Bela Lugosi on YouTube

- Requiem for Bela Lugosi on YouTube

- A Look Back at Lugosi on YouTube

- Home Movies of Bela Lugosi on YouTube

- Bela Lugosi

- 1882 births

- 1956 deaths

- People from Lugoj

- 19th-century Hungarian people

- 20th-century Hungarian male actors

- 20th-century American male actors

- 19th-century Roman Catholics

- 20th-century Roman Catholics

- 20th-century sailors

- American male film actors

- American Roman Catholics

- American people of Serbian descent

- American socialists

- American trade unionists

- Austro-Hungarian Army officers

- Austro-Hungarian military personnel of World War I

- Burials at Holy Cross Cemetery, Culver City

- Hungarian emigrants to the United States

- Hungarian expatriates in Austria

- Hungarian expatriates in Germany

- Hungarian male film actors

- Hungarian male silent film actors

- Hungarian male stage actors

- Hungarian Roman Catholics

- Hungarian people of Serbian descent

- Hungarian sailors

- Hungarian trade unionists

- Hungarian socialists

- Male Shakespearean actors

- Naturalized citizens of the United States

- Universal Pictures contract players